Mikhail Bakhtin, Dialogic Form and Metaphor

by Mark Staff Brandl

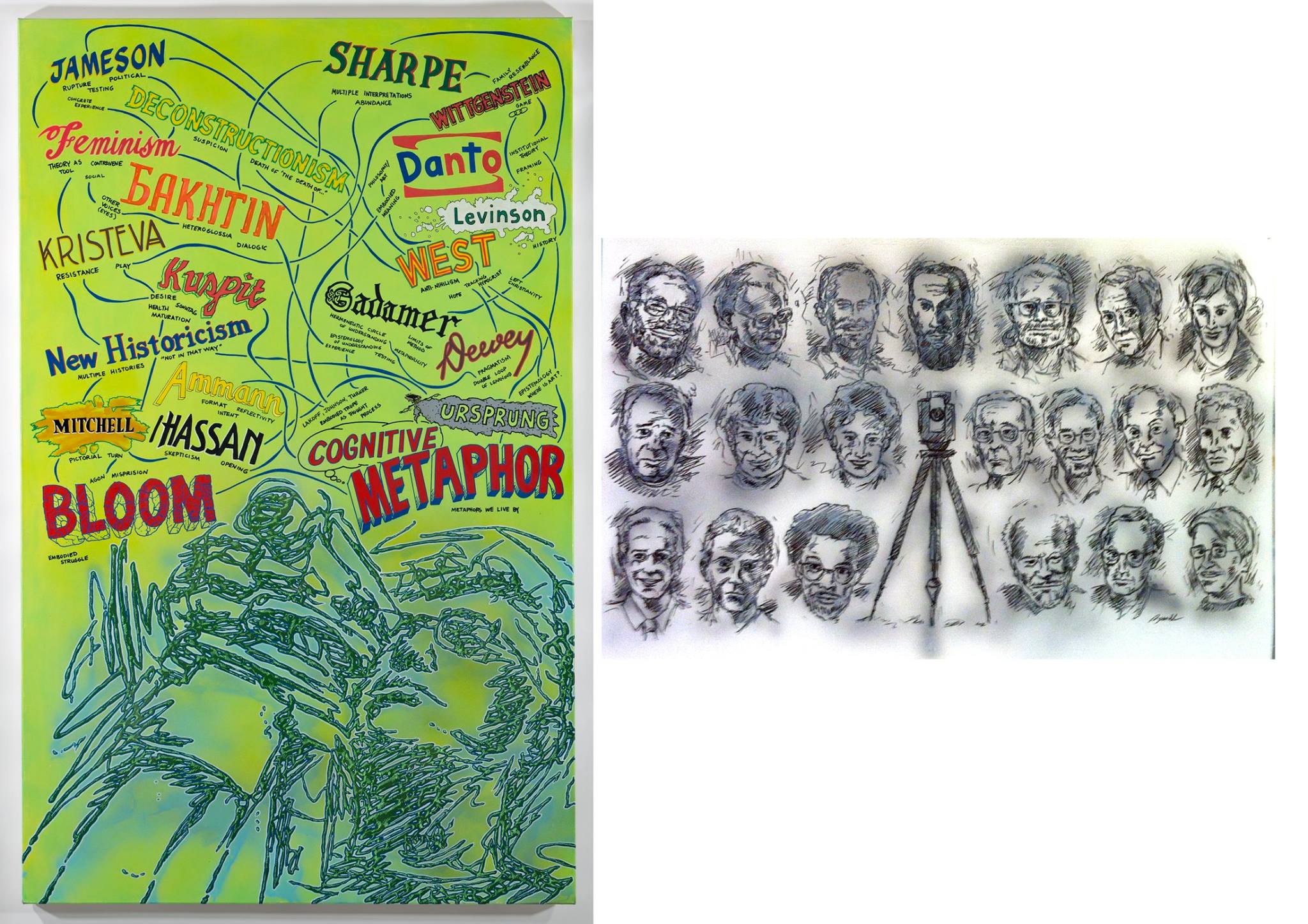

All metaphor(m)s, central tropes, are framed by an implicit ‘for instance.’ A literary theoretician who has served as an inspiration behind my metaphor(m) theory in particular and my thought in general is Mikhail Bakhtin. This theorist, perhaps unfortunately, has been claimed by all. Theorists of every bent seem to find him a compatriot. This may be a result of “confusion,” as Gary Saul Morson suggests in his essay “Who Speaks for Bakhtin?” due to Bakhtin’s “peculiar, elusive, even weird biography and style, not to mention his breadth of interest.”1 However, Bakhtin is important because he invented several genuinely remarkable ideas; ones which are insightful and serve as necessary solvents for unproductive philosophical notions gumming up current theorizing. More positively stated, Morson goes on to assert that reading Bakhtin encourages us to make a “meaningful escape from an endless oscillation between dead abstractions.”2 This is a better explanation of why he has such importance to me and so many others.

Bakhtinian notions which have helped inspire me include his sense of the living fluidity of expression; his concepts of heteroglossia, polyphonic form, and dialogic form; his insight that these may engender the liberation of alternative voices; and his presentation of the carnival as a suggestive metaphor.3 In Bakhtin’s view, language is not a neutral static object (à la Ferdinand de Saussure). Language, especially creative language, is an “utterance,” a social act of speaking, involving struggle, ideology, class, speakers and listeners. I see this as describing the socio-political context of the development of artistic tropes. Therefore works of art are not “uni-accentual.” That is, they are not limited to having simply one of a small range of possible meanings. Rather, heteroglossia defines the state of meaning in all discourse. By this, Bakhtin means that a multitude of voices naturally resonates within each utterance. This is the chief source of richness in all expression and, prescriptively speaking, should be emphasized and built upon by authors.

Nevertheless, he believes, heteroglossia is generally suppressed, if unsuccessfully, in order for those in power to feel comfortable in their attempts to control others. Bakhtin supplies us with an artistic version of the philosophical necessity of accepting belief in the existence of other minds. Artists’ works interweave multiple social points of view as well as being individual expressions. Likewise, a specific artistic trope is only possible within the confines of the time and place where it is created, thus it reflects the cultural and temporal dependency of all tropes, even Lakoff’s so-called foundational metaphors, at least in their concrete manifestations. My theory of metaphor(m) must too, then, be framed by context. Yet I see this frame like the walls of an arena. Within its confines lie the elements with which the thought-game can be played, both in and against the rules.

Heteroglossia may be envisioned as an unsystematic, almost chaotic struggle of a variety of voices. Likewise, the “strongest” artworks (to return to Bloomian terminology) are many layered and composed, yet often not truly systematically unified, I contend. I see this in the novels of James Joyce, some of Pablo Picasso’s most important works such as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, and the early installations of Dennis Oppenheim such as Early Morning Blues.

http://www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=79766

Pablo Picasso,

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,

oil on canvas,

1907,

243.9 x 233.7 cm / 96 in x 92 in

http://www.dennis-oppenheim.com/web/artwork/content/images/img_37.jpg

Denis Oppenheim,

Early Morning Blues,

room installation,

mixed media,

1977,

dimensions variable,

5 ft diameter aluminum record player, 10 ft diameter neon hotplate

Continuing this line of reasoning, Bakhtin both asserts heteroglossia as a foundational truth and promotes its exploitation in writing. This is approach I used in my dissertation as well. Bakhtin finds an exemplary version of heteroglossic literature in the novels of Fyodor Dostoevsky. This author created what Bakhtin terms a new polyphonic or dialogic form. The various points of view which arise in a novel, within or between characters, are presented and utilized, but not hierarchically ordered. The invention of a unique self in art, of a central trope comes about through antithetical struggle, as I have repeatedly asserted, hence I am frequently tempted to use the term dialectical when describing it. However, this term suggests very ordered conflicts between simple pairs of contradictions, which then result in clear syntheses. The formation of artistic tropes, and creative thought in general, I find accurately described in Bakhtin’s terms. An artistic trope is dialogically forged and used. It revels in the interplay of equivocal, interlocked meanings. There are multiple theses and antitheses yielding no synthesis, but rather the opportunity for even more conflict. Such struggle is subversive and liberating. Similar to Bakhtin, I define my theory as being fundamentally true of the arts, and yet I am also propagandizing for its more conscious and proficient application.

Finally, Bakhtin’s use of the carnival as metaphor is attractive, albeit perhaps too often cited. Bakhtin asserts that literature can undermine the dominant conventions and rules through jesting and unruliness. In our time such festivities have disappeared, been commercialized beyond use, or have degenerated into exploitative, sexist, drunken sprees. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri envision plurality itself as a potential carnivalesque arena of liberation in their book Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire, one resistant to neo-conservative globalization and homogenization. 4

I believe the spirit of the carnival, as Bakhtin imagines it, lives on in the creation and enjoyment of tropes. Raman Selden describes this spirit as “collective and popular; hierarchies are turned on their heads…; opposites are mingled…; the sacred is profaned. The ‘jolly relativity’ of all things is proclaimed.”5 In my theorizing, the carnival as trope is replaced by the trope as carnival. Borrowing a phrase from Morson in his essay “Tolstoy’s Absolute Language” wherein he describes the novel in Bakhtin’s eyes, we might say that all central tropes “are framed by an implicit ‘for instance’.”6