Art History: First, the Time-Lines.

by Mark Staff Brandl

While I am primarily a visual artist, a painter and maker of what I call painting-installations, I am also an art historian (Ph.D. in art history and metaphor theory at the University of Zurich). Nevertheless, I have been known to criticize art history as it is taught. My criticism of the typical timeline models can be found here.

I will discuss my own “Braided Rope Model” (created together with John Perreault) in detail in the future. Right this moment, I would like to make certain that we are all on the same page, after a fashion, when discussing or using art history here on the Metaphor and Art website.

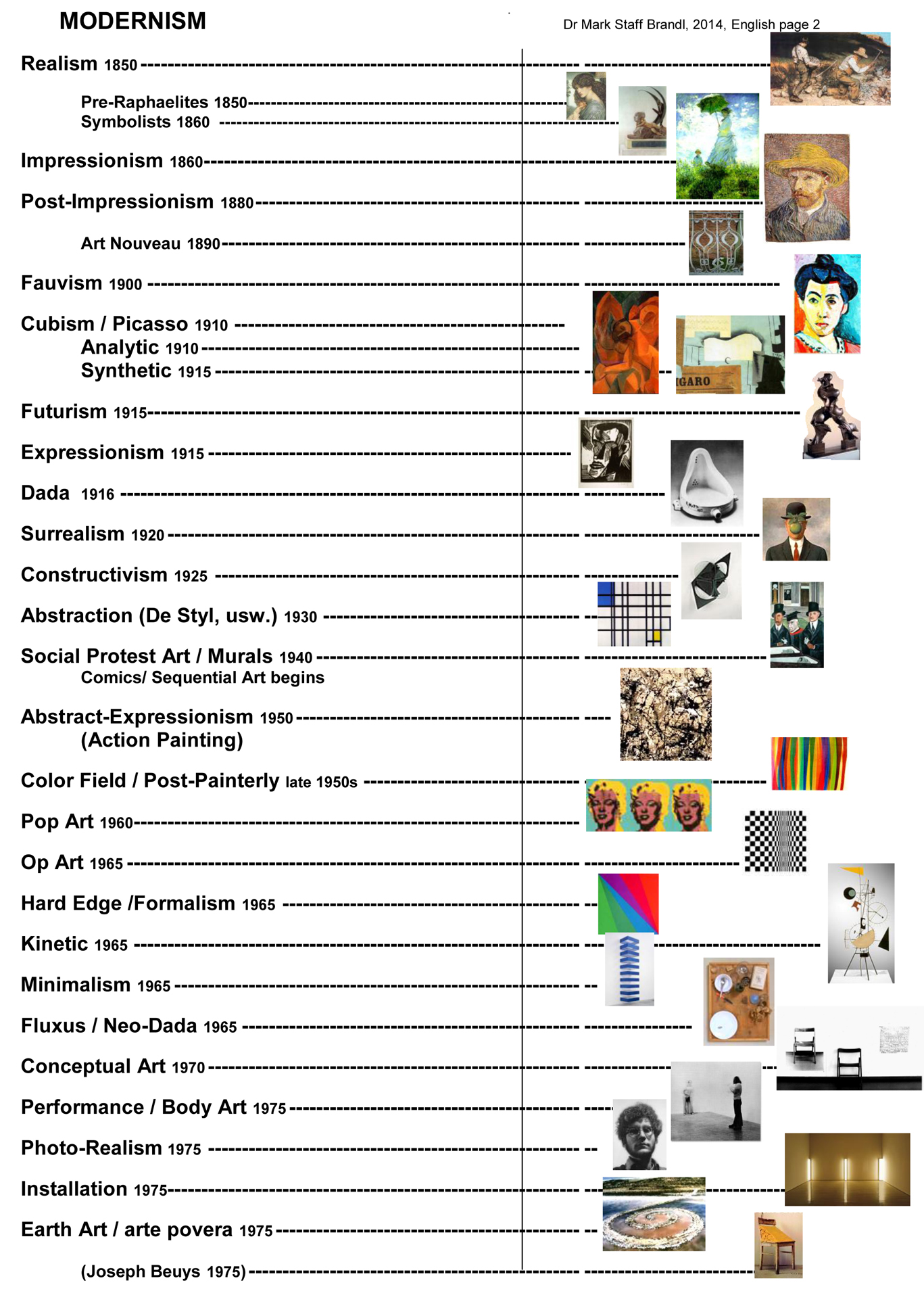

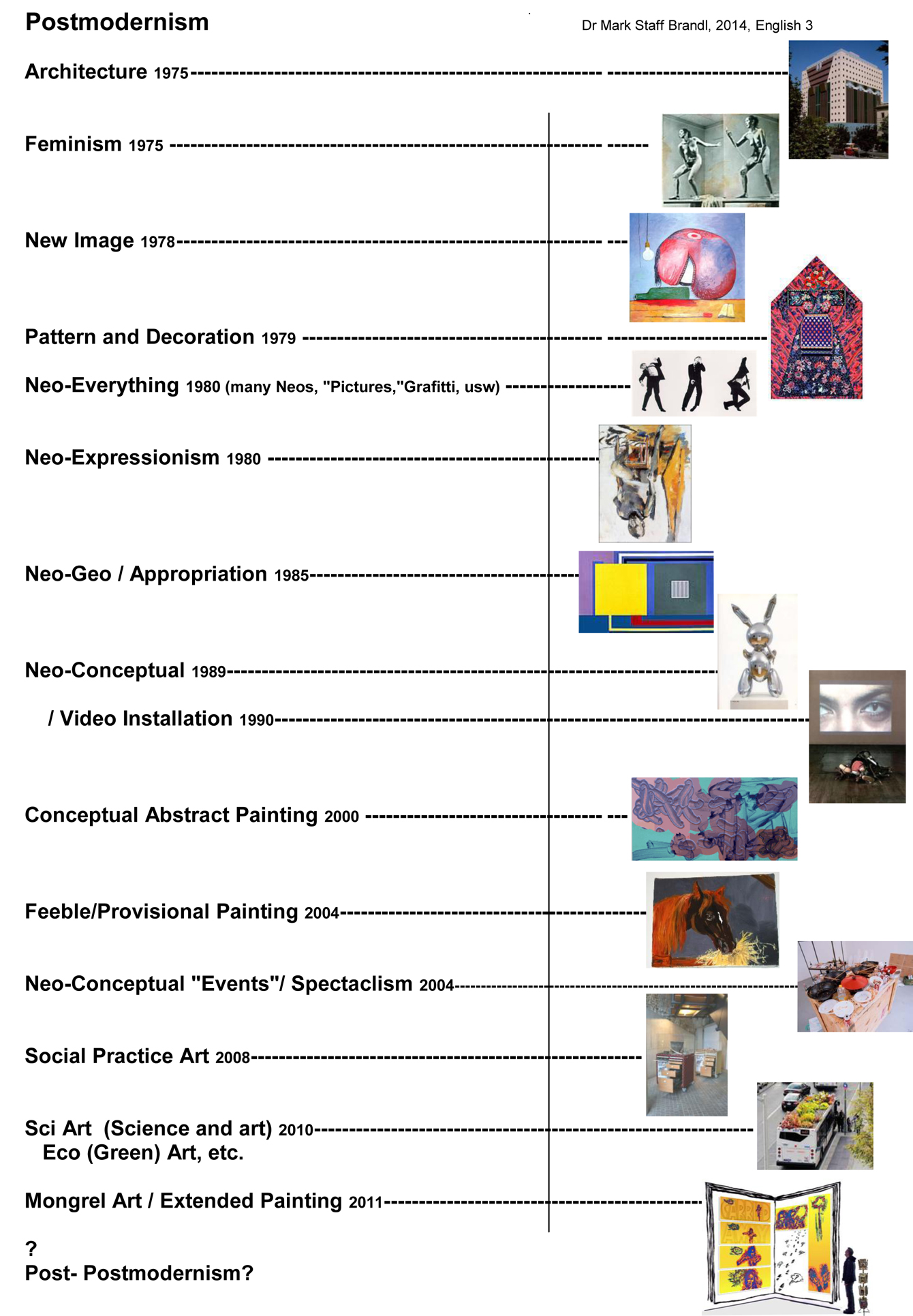

Thus, I am simply presenting my “Quicky Art History Times” to be used as reference. The first page is the entire history of art from Prehistoric through now, Postmodern. In a grossly superficial fashion, of course, to fit on one page. the second sheet is a zoom-in close-up of the entry “Modernism” alone. The third a zoom-in to “Postmodernism.” This might indeed be the most interesting to many readers and viewers, as there are hardly any books on the entirety of this subject, and those that do discuss it are generally highly selective, limited and indeed often propagandistic attempts at promoting one single contemporary style, usually Neo-Conceptualism. The best book is Irving Sandler’s Art of the Postmodern Era, yet it is huge, 636 pages, and expensive; a book essentially for other art historians.

I lived through this era. I was doing my BFA in Late Modernism, began my art career and MA in beginning Postmodernism, finished my Ph.D. in the continuing Postmodernism — and I continue until now, what I would like to hope is Late Postmodernism. A note on the differences between these two eras:

I, and most international art historians, see Modernism in visual art as roughly, very roughly, from the 1830s to 1979 (yet actually still continuing now, as some major practitioners are still alive and active, — indeed all periods and epochs always overlap anyway ). The (sub-)era known as Postmodernism began roughly 1970–79 or 80. Philosophical and literary proto- and prefigurations began in the 60s, yet there are always earlier precursory to be found for any situation, which is why we have the prefixes ‘pre-’ and ‘proto-’ in our languages.

This era (from, very roughly, 1979/80 till now, as stated), is a transitional period very similar to, on the one hand, the transitional period now called Mannerism after the Renaissance and, on the other, the transitional period called Academicism shortly before Modernism began. (I have discussed this similarity here: “Mannerism is Now”).

Postmodernism overlaps Late Modernism, yet is clearly AFTER Modernism in several philosophical, historical and visual ways. Thus, literally “Post-Modern,” generally trendily elided to Postmodernism in emulation of French. Modernism, especially in its the “Late” form, is progressively more reductive. Abstract Expressionism, Pop, Op, Kinetic, Minimalism, arte povera, Land Art and especially Conceptualism are all clearly Modernist in their goals and approaches, albeit in vastly differing fashions — this gets us to 1979. Postmodernism began (quite hopefully I might add) with architecture and Feminist art. Charles Jencks established the word in the visual arts, especially architecture, in a series of books from about 1977 onward, especially the artist-read favorite What is Post-Modernism? (The term had long had vogue in literary theory, however.) At the same time, the first wave of Feminist artists began introducing hard-hitting, clear, even heavy-handed content. We beginning artists clearly saw that this was “not” or ”after” Modernism in someway. All of this and more lead to the beginning of Postmodernism taking over what until then had simply been termed pluralism. How Post-Modernism later congealed into a permanent state of academic Neo-Conceptualism as it came under the influence of trendy French Poststructuralism and other literary theory, the power-grab in art schools of the at-that-point out-of-power Conceptualist professors, the demise of art criticism and the rise of the art curator, is another story. Soon to be told.

And do not forget: Yes history repeats, after a fashion. But it is primarily a tool for thought. Everything is always new, when it is personalized and arises out of real, lived experience in the time and culture of the creator. One gets a historical perspective, to an extent, by using history as a instrument for contemplation and making analogies. Thus once again, Mark G. Taber and my addiction to metaphor as a thought process.

History is not a limitation unless you make it so. We need this form of conversational, perhaps even argumentative, homage AND transgression. The relations among cultural aspects can be seen as not simply oedipally belligerent, but not as untroubled either: a model which presents the possibility of a productive transmission of culture, grounded in modes of vernacular interchange. This authorizes, in a sense, successors who also alter the traditions without being obliged to symbolically slay them. This is not a burden of tradition — when you examine the world of jazz you will find a culture and a model that has been, and remains a hot bed of innovation. Rock carried that on in open loud passion and interracial influence. Hip-hop now continues cross-generational cultural transmission by providing a new lyric to older tunes, quite literally. We in the visual arts can do likewise with our cultures.

In my opinion, as an artist, one can do whatever arises out of the true experiences of your own background. Your sources must be personal and “earned.” Cognitive metaphor theory proffers a mode of thinking which can be applied to the analysis and creation of art, while accentuating the efforts of the makers of these objects. After the object-only orientation of Formalism, after the medium-only focus of Deconstruction, this may lead to a feeling of liberation, of agency. Nevertheless, my metaphor(m) is a theory which brings with it a new sense of the the past. Whereas the Formalist Modernists felt free from the past and the Deconstructivist Postmodernists are endlessly tangled in an inescapable present, authors and artists as viewed through my cognitive metaphor theory are directly responsible for fashioning their own tropes through the processes of extension, elaboration, composition and/or questioning. Once again, more about this will arise in future articles on this website.

Artists in particular should learn art history. Such knowledge does not give rise to fear, to a burden of the past, as is frequently fretted (particularly by Europeans), but rather the opposite. One has more of a burden of the past when one knows little to nothing of history. A vaguely threatening cloud hangs over your thoughts and your work. When you know it you can respect it by wrestling with it. Artists develop their own, perhaps idiosyncratic, inheritance by knowingly, actively re-writing the timeline. Creators are able to discover their preferred precursors, find their own artistic fathers (and fortunately, ever increasingly, mothers). The friendship and conversation with the dead that Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset saw in history allows creators to find as much sustenance in Goya as in their contemporaries. Yet such conversance also imparts opportunities for antithetical, critical historical and cultural awareness.

I think, as well, that too many people fixate on the term “Postmodern,” thinking that by denying it, or rewriting history in some way, they can eliminate it. The Big Question we should be pondering is how to mature, to get “healthier” to use Donald Kuspit’s term. How to use art history as a tool for making analogies to help us get onwards to a situation beyond the current malaise of disintegrating academicism.

The overview I have illustrated below is the most, logical and international view. The best for reference and learning; it is correct, yet vastly limited. We do not need to ignore history but to expand it (see my critique and braid theory once again).

Please use these charts. They are the foundational reference in all the art historical discussions on this site.